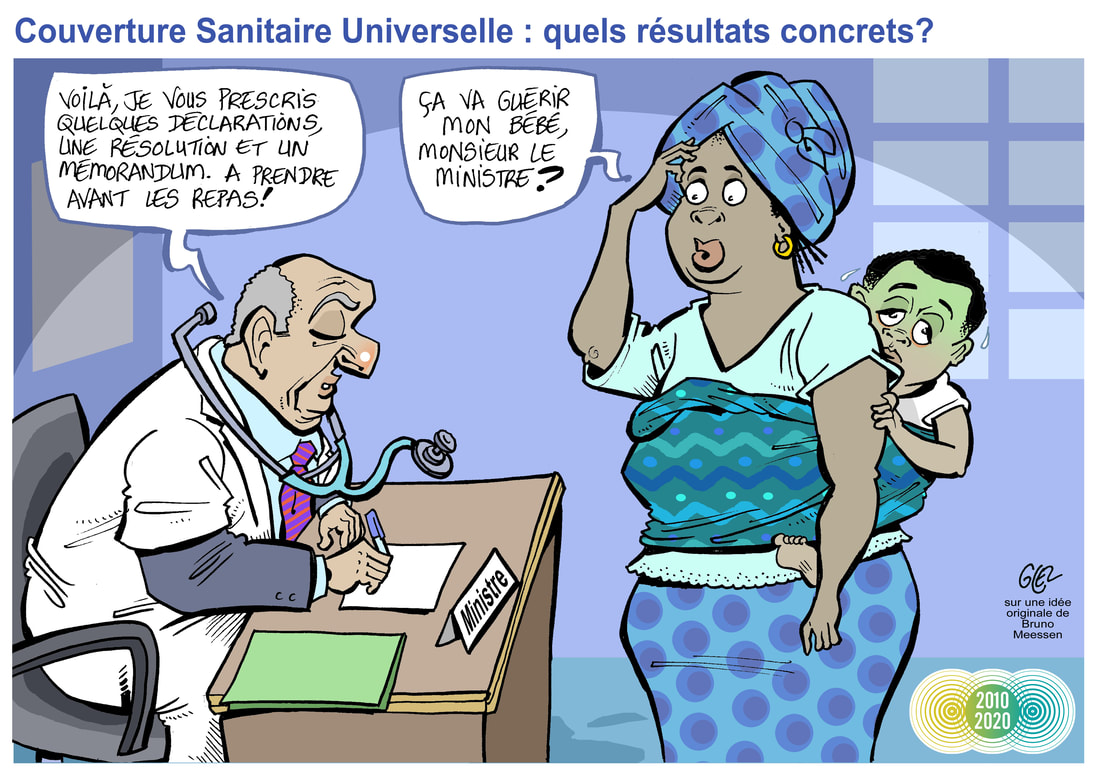

La politique de gratuité des soins (pour les femmes avant, pendant et après l’accouchement et pour les enfants âgés de moins de cinq ans) couplée avec le Financement Basé sur la Performance au Burundi figure à l’ordre du jour du triple anniversaire célébré sur Health Financing in Africa. Dans ce billet de blog, Alexandre Nimubona présente sa lecture personnelle de cette politique dans et dégage quelques enseignements pour l’agenda de la Couverture Sanitaire Universelle (CSU).

Une forte utilisation des services de santé

Au Burundi, le consensus est que la politique « Gratuité et Financement Basé sur la Performance » (G-FBP) a contribué à une meilleure organisation et un meilleur accès des services de santé. Ces améliorations ont conduit à une forte augmentation de l’utilisation des services de santé. Au cours de cette dernière décennie, les nouvelles utilisations des services curatifs / habitant / an sont passées de 2,3 à 5,1 chez les enfants âgés de moins de cinq ans et de 0,7 à 1,9 pour tous les âges confondus. Selon l'annuaire de statistiques, les accouchements en milieux de soins assistés par un personnel qualifié sont passés de 60,7% à 98,5%. La population protégée contre les difficultés financières d’accès aux soins a doublé, en passant, selon les estimations et critères des enquêtes EDS, de 10% à 23%. Comme résultats, la mortalité intra-hospitalière est passée de 3,1% à 1,2% ; la mortalité maternelle a diminué de près d'un tiers (désormais à 334 déces maternel pour 100.000 naissances) et le taux de mortalité infanto-juvénile est passé de de 96 à 78 pour mille naissances vivantes.

Un gouvernement et des partenaires loyaux à la politique

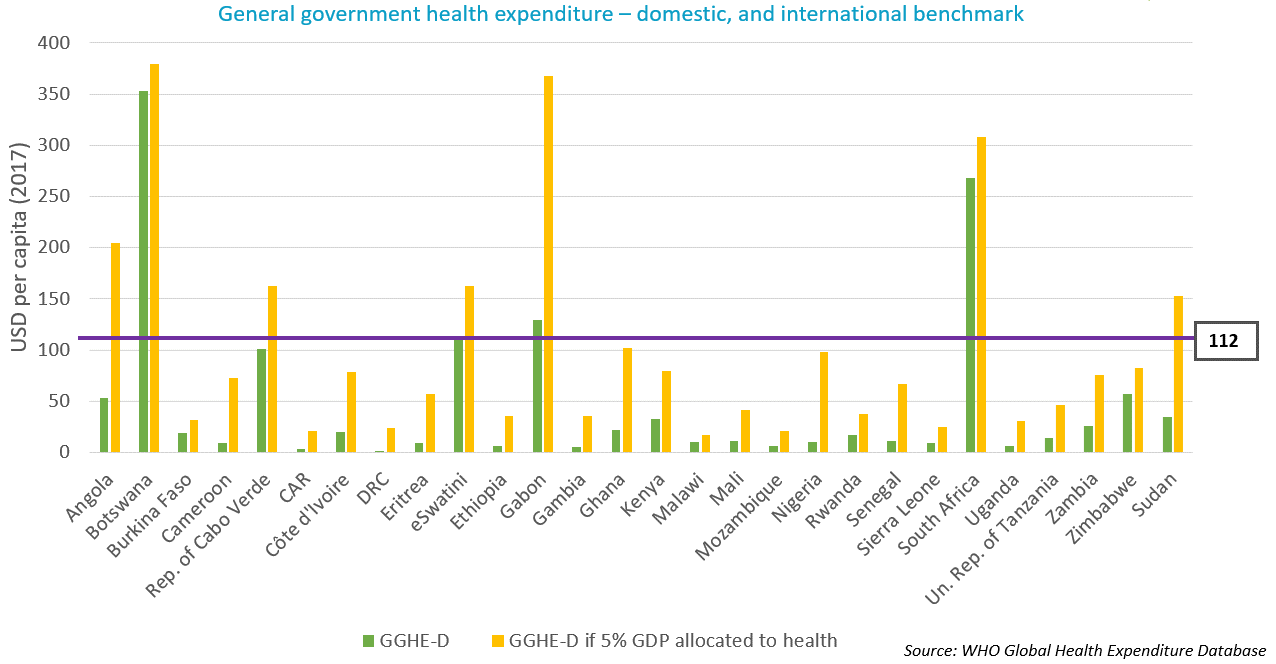

Le Gouvernement burundais a fait de la G-FBP une de ses priorités politiques nationales ; il a veillé à ce que les procédures techniques et financières de l’aide étrangère pour la santé s’harmonisent et s’alignent sur la G-FBP. Chaque année, le budget de la G-FBP est discuté et voté au parlement. Ce budget qui s’élève à 2,3USD du PIB/habitant en 2020-2021 est resté stable sur ces 10 ans, en dépit des difficultés économiques que le pays traverse. Pour leur part, tout de suite, les partenaires se sont lancés dans la mise en commun des compétences techniques afin de garantir une capacité nationale pour le management du FBP. Etat et partenaires se sont aussi accordés sur une mise en commun virtuel des fonds de la G-FBP à redistribuer aux différentes structures de mise en œuvre en fonction de leur performance.

Quatre éléments remarquables

Dans l’ombre de la fusion entre gratuité et FBP, quatre caractéristiques plus discrètes de l’expérience burundaise (Jean-Benoît Falisse a parlé d’hybridation) méritent l'attention.

1. Le Burundi a institutionalisé et « étatisé » l’achat de la performance en mettant en place une Cellule Technique Nationale (CT-FBP), avec une décentralisation technique au niveau des Comités Provinciaux de Vérification et de Validation (CPVV). Composé d’experts contractuels du FBP et fonctionnaires locaux de l’Etat, la principale spécificité des CPVV est qu’ils placent les acteurs d’achat au plus près du terrain pour un « achat responsable ». C’est-à-dire, un achat qui concilie durablement les deux grandes sphères de la G-FBP que sont la quantité et la qualité, en vérifiant si les quantités prestées sont à la hauteur des espérances projetées et dans le respect des normes de qualité.

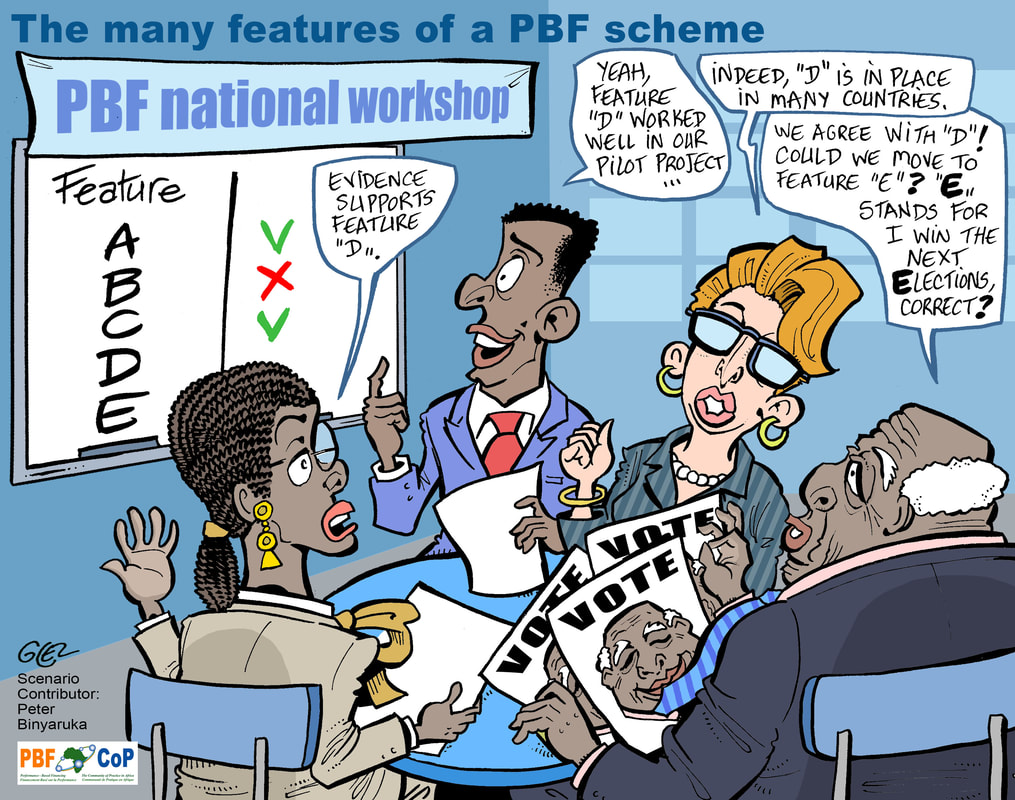

2. Le volet FBP de la politique est dynamique – dans ce sens, un pas a été fait vers l’« achat stratégique » : l’instrument (FBP) est adapté au fil des apprentissages. Pour ce, quatre changements (à intervalle moyen de 2,5 ans) dans les critères d’achat ont été effectués lors des différentes modifications du manuel de procédures de la politique G-FBP :

- Première modification (2011) : Révision à la hausse des barèmes et introduction de pénalités financières en cas d’un score pour la qualité globale de moins de 50% (Malus Qualité) ou d’un taux de fausses déclarations supérieur à 5% des prestations quantitatives.

- Deuxième modification (2014) : Redéfinition du paquet et des indicateurs d’activités du premier et deuxième échelon de soins, puis retrait des « indicateurs de prévention » du deuxième échelon ; révision à la baisse des tarifs des indicateurs quantitatifs et augmentation des subsides pour la qualité ; enfin mise en place d’une approche « triangulation des données » pour réduire les fraudes.

- Troisième modification (2017) : Mise en place de la G-FBP de deuxième génération, avec à nouveau, une révision des barèmes des indicateurs quantitatifs (jusqu’à 30% d’augmentation pour le premier échelon de soins) ; opérationnalisation de l’achat au niveau communautaire par stimulation et rémunération des réponses locales (sensibilisation pour l’utilisation des service de santé, visites et soins à domiciles, accompagnement des malades vers les structures de soins…) aux besoins de santé via le FBP communautaire.

- Quatrième modification (2020) : Après le constat que le Malus Qualité privait les formations sanitaires de ressources financières indispensables et les contraignait à des stratégies indésirables (ex. non-respect de la gratuité) affectant négativement la qualité et l’abordabilité des soins, « abandon du Malus Qualité » ; mise en place d’une stratégie de maîtrise des coûts plafonnant les quantités des prestations achetées par la G-FBP à 300% de la cible attendue pour les consultations des enfants âgés de moins de cinq ans et à 120% pour le reste des indicateurs.

4. La G-FBP a mis en place les « outils de régulation standards » tels que les fiches de déclaration des prestations mensuelles et les grilles périodiques d’évaluations de la performance à tous les niveaux du système de santé. Ces outils sont utilisés pour les auto-évaluations périodiques des acteurs de mise en œuvre en vue d’une amélioration continue de leur performance.

Deux chantiers à mener

L’analyse des progrès réalisés permet de discerner aussi deux chantiers sur lesquels il nous faut encore avancer pour augmenter l’accessibilité et l’acceptabilité des services de la G-FBP :

1. Les « mécanismes d’équité », jusqu’à présent limités à un seul critère géographique au niveau provincial, doivent évoluer jusqu’au niveau individuel pour rendre le système de santé plus juste. L’idée serait de mieux prendre en compte les contraintes propres à chaque formation sanitaire dans la couverture des besoins de la population de référence. Il est ainsi important d’imaginer qu’une formation sanitaire desservant une population particulièrement pauvre reçoive un subside financier supplémentaire.

2. Le « partenariat public-privé » conclu au cours des 10 dernières années a montré que les prestataires privés enrôlés n’avaient pas de capacité financière pour soutenir les efforts du Gouvernement et qu’au contraire attendaient de ce dernier un appui financier pour leur business. Cet appui n’étant pas institutionnalisé, il est aujourd’hui « pris » – il s’agit par exemple de médecins du service public ayant une pratique duale et facturant leurs prestations au plus cher dans leur pratique privée. Pour réussir un partenariat positif, le Gouvernement burundais devrait, selon nous, combattre ces pratiques par la régulation et une démarche cohérente sur les tarifications, y compris dans le secteur privé.

Trois obstacles à surmonter

Selon mes observations faites en 10 ans de mise en œuvre, trois problèmes structurels affectent la politique G-FBP :

1. Une forte incertitude de nature financière s’est manifestée sous forme de retards de remboursements des prestations. Cela fragilise les décisions budgétaires au niveau des formations sanitaires en altérant les liens entre planification et exécution (l’élaboration des plans d’action tient compte des périodes probables de remboursements qui ne sont pas toujours respectées) avec comme principale conséquence, des ruptures des stocks en médicaments.

2. Aujourd’hui, le Burundi est dépendant de ses partenaires pour l’évaluation des technologies de la santé. Depuis 2010, le stock des connaissances scientifiques a évolué et il y a certainement des interventions qui mériteraient, sur base de leur cout-efficacité, d’intégrer le paquet couvert par la G-FBP. Une capacité nationale, même de base, permettrait de guider la définition des paquets de prestations et l’allocation des ressources. Une mise à plat des dispositifs financiers permettrait aussi de régler le problème de duplications dans le paiement de certains soins (ex. les prestations remboursées par d’autres assurances étaient également payées par la G-FBP).

3. Une autre faiblesse en termes de capacité réside dans l’analyse et l’utilisation des données. Une vraie capacité à ce point est cruciale pour aller vers un achat plus responsable et stratégique. L’enjeu se trouve notamment dans la coexistence en parallèle de plusieurs bases et systèmes de données (entre autres les bases de données G-FBP, CAM, OpenClinics, SIDA Info, …).

Quatre vœux pour l’avenir

A mon sens, quatre actions restent souhaitables pour aller vers une CSU durable au Burundi :

- La mise en place d’une stratégie nationale de financement de la santé permettrait de mieux aligner le système de santé burundais sur les objectifs de CSU. Nous devons veiller à la meilleure articulation entre différents mécanismes d’assurance-santé avec la G-FBP, en progressant vers leur fusion ultime en un seul régime.

- L’interopérabilité des bases de données ou mise en place d’une base unique des données sanitaires pour tous les projets et programmes de santé à tous les niveaux, nourrirait la rationalité des décisions prises.

- L’instauration d’un système de comptes trimestriels de la G-FBP dans chaque formation sanitaire pourrait aider les gestionnaires dans la conduite économique de leur établissement.

- Un engagement renforcé du Gouvernement dans le financement de la G-FBP. C’est en effet à cet aune que l’«ownership» est à apprécier. Même si les décisions ne sont pas à son niveau, la CT-FBP pourrait peut-être améliorer son plaidoyer en exploitant mieux les données dont elle dispose (par exemple faire un suivi du taux de décaissement et alerter régulièrement les concernés).

Conclusion

Selon nous, la politique de G-FBP possède le dynamisme et la souplesse nécessaires pour induire des changements essentiels dans un système de santé fragile comme celui du Burundi. Cette politique a permis le développement d’une approche cohérente du financement de la santé : le financement interne se conforme à certaines exigences externes et vice versa ; ensemble, ils font progresser la performance du système de santé. Bien sûr, la G-FBP ne règlera pas tous les problèmes de santé, toutefois, elle a dessiné les premiers contours d’une CSU durable dans un des pays les plus pauvres du monde. Et c’est une belle réalisation.