Dr. Walter Kessler worked for Doctors Without Borders - Belgium (MSF) in the 1980s. Together with Eric Goemaere, he was one of the architects of the of the ‘health stores’ project, an experience that had greatly inspired the Bamako Initiative as the project was based on both cost recovery and community participation. Later on, Walter also worked on the implementation of the Bamako Initiative in Chad. He discusses these two experiences.

Can you start by telling us about the first project in which you were involved in, the “health stores"? What was the idea? In what context did it occur?

In 1984, during an exploratory mission in the sixth region of Mali (Timbuktu) and after several years of drought, MSF discovered a situation that was critical in every respect: socio-economic, sanitary, and food-wise. The decision was then taken to intervene and two things were set up: (1) a supply system of essential medicines for the health system; and (2) feeding centres for malnourished children. The centres were quickly operational and ran rehabilitation and nutrition education programmes. They also integrated other routine activities of the health centres. But it was not enough. Without massive food aid, the situation could only get worse. In a context of persistent drought, the population had exhausted all forms of food reserves, including seeds.

Events then precipitated: the donors came forward and MSF quickly became a major player in the widespread distribution of grains in the form of food-for-work activities. Food was given out in compensation for work that was organised following various community initiatives, such as the repair of water dykes or the rehabilitation of schools and health clinics.

To support food aid and the drug supply system, MSF also implemented a strategy of "health and drought stores". The idea was to create points for the supply of different basic items such as seeds, spare parts for irrigation pumps, or essential medicines for hospitals and clinics. It would then establish a buffer, a capacity of resilience of the supply system. This system had to be sustainable and a cost recovery approach was therefore chosen. "Stores" would sell their products.

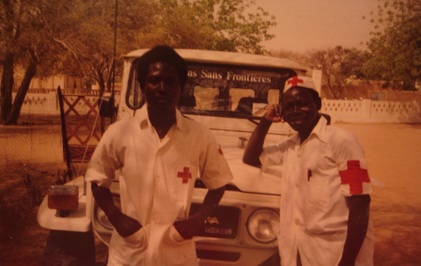

MSF medical assistants in Chad, 1984

MSF medical assistants in Chad, 1984 In fact, there first was a transition from the emergency "health and drought stores" to the "health stores". These structures were supposed to supply dispensaries and hospitals, given that the already existing “people’s pharmacies” could not do that anymore.

Health stores were accompanied by several innovations, at the medical level first:

- The concept of essential drugs was something new. The list of products used was that of MSF. The “people's pharmacy”, which was the traditional supply system, proposed wholesaler packages for some molecules, but shortages were common. Hence the import of stocks of drugs for the 5th and 6th and health region.

- Similarly, trainings on the use of essential drugs (prescription, dosage, etc.) were organized for the medical staffs.

- A system for recording visits was set up and operated at the health facility-level. Indeed, the rationale for the use of drugs should be based on the morbidity encountered.

And what was new in terms of health services management? Did community participation originate in food-for-work activities?

Yes, building on community experiences during the food-for-work emergency phase of 1984, MSF set up the first health committees Mali. In fact, we transformed the food-for-work and nutrition committees into committees around the health centres, each covering a catchment population. The committee was supposed to be involved in the management of the stock of medicines and ensure the proper use of the means available at the health centre-level. It was composed of members of the community.

Community participation was an opportunity created by the extremely precarious situation in which the population was. Food-for-work was addressed to communities and was thought of as compensation against work for the common interest. This approach enabled us to achieve the rapid distribution of a large quantity of food to the final recipients. The flexibility of an organization like MSF has probably improved the efficiency of the system, but at the same time, public structures were partially bypassed. This caused frictions but the inclusion of district chiefs and village health workers in the health committees helped us avoid problems. The involvement of the whole community, including the medical staffs and authorities, in the project allowed everyone to save face.

How did the health store strategy work? How was the idea received by the population?

This system quickly proved efficient in terms of drug supply. The pyramid –one store per region, and then stores at the lower level (the “cercle”) that cater for health centres– was effective, and so was the procurement system that was flexible and required only limited consultation with some suppliers known for their reliability. Through the new system, out of stocks stopped.

On the ground, there was no visible problem with the acceptance of health stores and this especially because of the situation; who would dare to question a program that caters effectively for an entire area in an adverse socio-economic context? Conversely, it is difficult to say whether all the actors really supported the concept. It is likely that the administration of Public Health was divided on the issue: on the one hand because it disavowed the existing system and on the other hand because of the too important place of MSF in the implementation and management.

Obviously, the speed of implementation and the effectiveness of the system aroused the curiosity of other donors and international organizations. Given the situation, the involvement of the population was -among others- opportunistic, but it fit perfectly with the concept of Primary Health Care advocated at the Alma-Ata conference.

Later on, the Bamako Initiative was inspired largely on the "success story" of health stores. Its founders believed that with this strategy, health for all by the year 2000 was at hand. However, we were quickly disillusioned. At the time of the Bamako Initiative, the health stores had not gone through their “sickness of youth” and it was unclear whether the concept as such, partly based on community participation, was actually viable in the medium and long run.

Based on your experience, do you feel that community participation was ‘spontaneous’?

In times of scarcity and famine, when everybody first works for their own survival and the survival of their relatives, community participation could never be spontaneous. Similarly, in a less dire situation but still marked by relative poverty, community participation without an immediate benefit for oneself or one’s family seems illusory.

Community participation had been requested to facilitate the delivery of aid and then organize the management of health activities. I think this participation was neither entirely spontaneous nor completely imposed. It was naturally organized around the revitalization of health facilities. With food-for-work, nutritional rehabilitation, and the supply of drugs, the benefits of participation were immediate and visible.

Let's talk about your experience in Chad. What were the differences with Mali?

MSF had already begun the supply of essential drugs to Chad during the civil war in the 1980s’. Our activities were gradually extended over a large part of the territory until the mid- 90s’ (I left Chad in 1995); there was a very serious shortage of skilled medical staff. Driven by the circumstances, MSF became a major player in the health pyramid, and was completely integrated to it.

The establishment of community participation in the prefecture of Mayo-Kebbi in 1989 took place in the context of a larger project of revitalization of the entire health system that included the rehabilitation and extension of infrastructures, the revitalization of district hospitals, and support in medical supplies and staff training. From the outset, community participation was oriented towards the active participation of the population in the management of health centres. This management was mainly about the revenues generated through curative consultations in order to cover the cost of medicines.

Revenue management was provided by a person designated by the health committee. This system was encouraged and supervised by the head doctor. The remoteness and lack of competence in the field did not allow for other alternative for the management of relatively large amounts of money; direct management by the medical staff was not a credible alternative. Revenue management remained risky because there often was no way to deposit money outside the health facility.

In an interview on this blog, Agostino Paganini declared that the Bamako Initiative died long ago. What is your take on that?

It is impossible for me to know what our projects have become, especially against the background of the tragic circumstances the region is going through. However, it seems that community participation as conceived in this time is fragile and transient. The heavy investment that is needed for community mobilization and voluntary participation to the committees is hard to sustain and inevitably leads to the depletion of the initial enthusiasm. The “bureaucratization” of some positions in the committees, such as treasurer or manager, often announces the beginning of a general decline in community participation.

In situations I have experienced in countries facing socio-economic and / or political stability and security issues, participation is not spontaneous and does not originate in local initiatives. It is rather part of intervention and support strategies, it is genuine good intention but it is not necessarily in phase with the problems of the target population.

Community participation, as long as community mobilization is supported and regular, can be an interesting vantage point to address populations’ need and take action. Yet, the survival of such initiative is directly related to the duration of the projects/interventions.