On 25-27 April, WHO Geneva organized a global meeting entitled “Strategic purchasing for UHC: unlocking the potential". In the follow-up of this event, I published a first blog post focusing on what a purchaser should do to act as a strategic purchaser (SP). In this second post, I focus on the responsibility of the stewards of the health system. Most of the hyperlinks refer to power points presented in Geneva.

Recently, an expert wrote to me: “many people remain confused about what strategic purchasing is and we need to think carefully about how to communicate it to different audiences”. I cannot agree more. As I was reorganizing my notes after the Geneva meeting, I felt myself the need to better map where SP takes place in a health system.

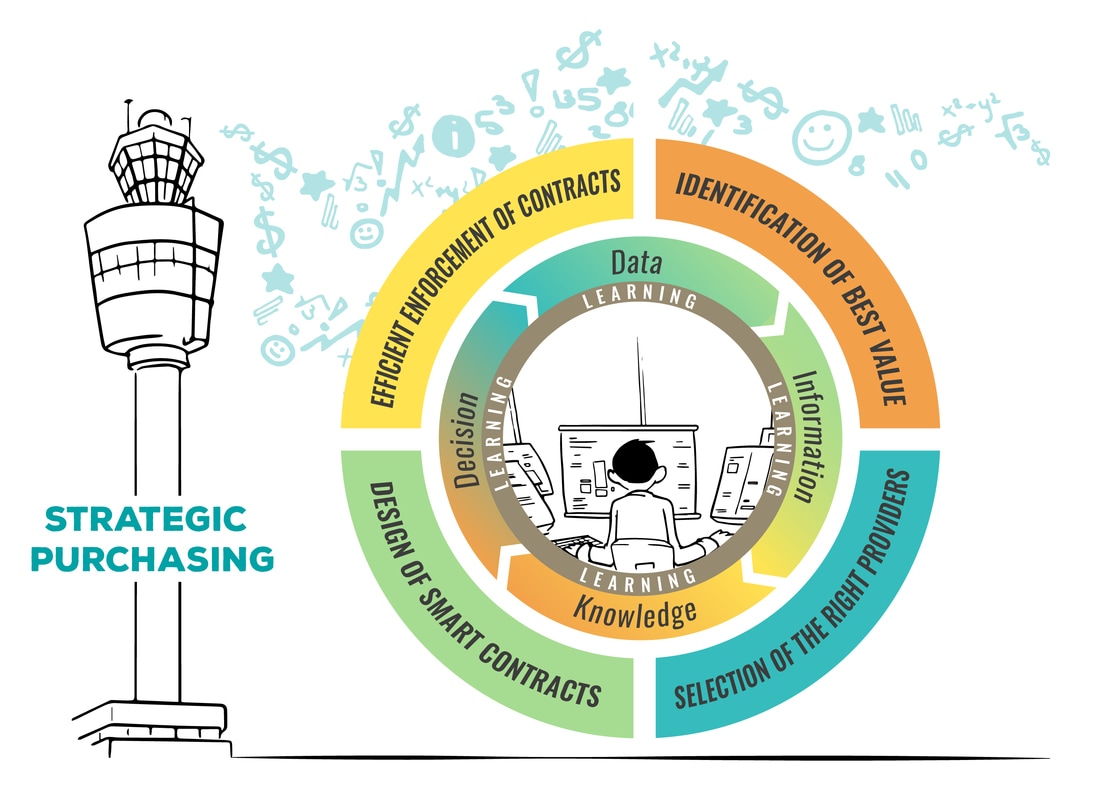

I wonder whether it would not help us to conceive SP conceptually around two main poles: the purchasers and the stewards. In a first blog, I sketched what a purchaser has to do to purchase strategically: it has to use information optimally (i.e. learn) while engaging in four complementary sets of actions: identification of best value, selection of the right providers, design of smart contracts and efficient enforcement of these contracts. I also explained that these sets of action and the related cross-cutting learning processes consume resources. Only some purchasers have the means (resources and a large pool of beneficiaries) to invest significantly in strategic purchasing.

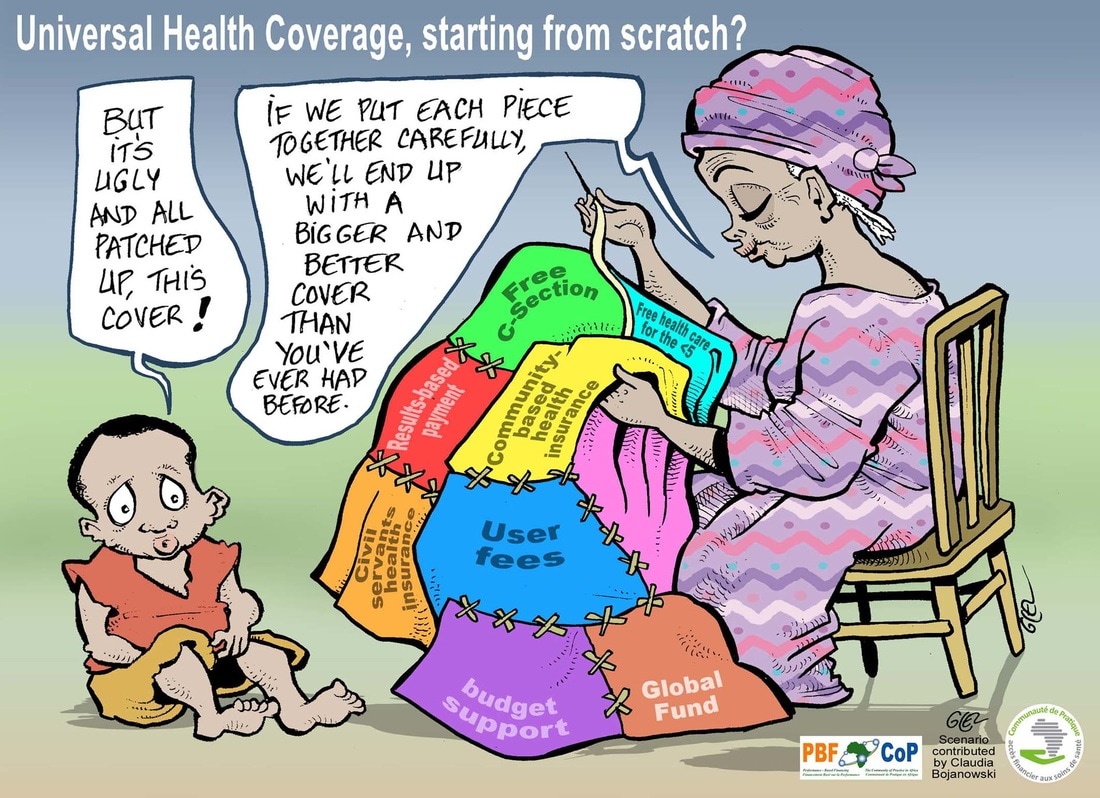

This limits the number of ‘potential’ strategic purchasers. Still, in many health systems, especially in LICs, there is a plethora of purchasers, strategic or not. This profusion harms the performance of the health system and affects progress towards UHC. At the Geneva meeting, it became clear that this is actually the main challenge.

Why fragmentation is also an issue for SP

It is well-known that fragmentation hampers risk pooling. But too much fragmentation also undermines the purchasing function.

A few years ago, we organized an online brainstorming in two communities of practice: “If we were to do a multi-country research project to enhance the UHC agenda, what should be the top priority?” Votes by our members were unambiguous: according to them, we had to document the high fragmentation of health financing in their countries. With CoP experts, we later conducted this study in 12 Francophone African countries. We counted on average 23 health financing schemes per country (still an underestimate, actually, as for practical reasons, we decided not to count each individual mutuelle). (1)

This abundance of schemes is a problem for purchasing for several reasons. Again, it helps to use the 4+1 sets of action to understand why this is the case: (1) purchasers will duplicate efforts in terms of value identification (or more probably: they will under-invest in it, as the intelligence effort requires advanced technical skills in public health, health economics and consultation); (2) all the purchasers may also prefer to work only with the same providers (those easy to contract), and overlook the providers costly to screen and engage with; (3) some purchasers may try to design smart provider payment contracts, but an uncoordinated set of provider payment mechanisms will often be very “unsmart” and actually establish contradictory incentives; (4) each purchaser, anxious to enforce its own contract, will also set up a specific accountability system, which will create a heavy administrative burden upon health facilities. So a situation of too many agencies, programs, schemes leads to duplication, gaps and information request saturation.

In Geneva, several sessions focused on the consequences of fragmentation on SP and the importance to address this issue. We heard about the cases of Burkina Faso and Morocco. We also learned a lot about how the stewards of the health system can contribute to SP.

The contribution of stewards to SP

The concept of stewardship was introduced in the WHO Report 2000. Nowadays, stewardship of a national health system is probably best conceived as a collective effort, with of course still a pivotal role for the Ministry of Health. Stewardship is about developing leadership, establishing coordination mechanisms, aligning collective action on the common vision, enforcing rules and aiming for coherence, among things, by promoting collective intelligence. Effective stewardship is key for the performance of the whole health system, but also for the performance of its sub-components, like the financing system and its purchasing function. This was also discussed during one half-day session in Geneva.

Stewards can contribute to SP in several ways. Again, to review them, the easiest is to take our 4+1 sets of SP actions (for an introduction to these 4+1 sets of action, see my previous blog).

Identification of best value: The stewards can take the lead on “value identification”, at least for the large part of it which is not specific to any scheme. Centralization of the task of quantifying population needs makes sense as the stewards anyway need this information for steering the whole system. Centralizing within one single agency the capacity for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) - i.e. the assessment of which medicines, diagnostics, clinical interventions or programs have to be part of the benefit packages provided by the different purchasers - makes a lot of sense as well. This is the model taken by the United Kingdom (NICE) or Belgium (KCE). It is not only a matter of returns to scale in terms of HTA expertise, it is also fully in line with the new WHO proposition to clearly distinguish between the three key steps of priority setting ( i.e. data, dialogue, decision – you can check out a recent CoP webinar by Agnès Soucat introducing this new vision here).

Selection of providers/purchasers: In my first blog, I explained how the purchaser could be strategic via the selection of providers to have a contract with. Actually, the stewards also have an important role to play in the selection of providers. First, it is up to the regulator to fix general rules upon entry on the health market and practice: what are the legal requirements to open a medical practice, a pharmacy; are there any specific fiscal regimes... These are important instruments to structure the health care market. Purchasers would also benefit from pooling efforts as for certification / accreditation of providers. The stewards have one extra function: they should also set the entry rules applying to purchasers themselves. For instance, what are the capital requirements and other legal obligations upon a privately-owned voluntary health insurance fund?

Design of smart contracts: as mentioned above, a combination of smart contracts is not necessarily smart from the overall perspective of UHC – the main goal of the stewards. Indeed, each purchaser is accountable to a specific set of stakeholders; it will design incentives to align the health facilities on the needs and objectives of these stakeholders – and they may differ from the overall public interest. Think of vertical programs whose operations and incentives sometimes undermine general health services! In Geneva, we discussed the importance of building a coherent and efficient provider payment mix extensively. This is clearly a responsibility for the stewards. Furthermore, the stewards have an important role to play in terms of making sure that the ‘smart contracts’ do not undermine interventions relying on other theories of change. This is particularly key for quality of care – how to balance strategies relying on high powered incentives (like Performance Based Financing) with, let’s say, the practice of quality circle?

Efficient enforcement of contracts: Verifying the performance of providers is costly. Many health systems are plagued with parallel accountability mechanisms. Again, it makes a lot of sense that purchasers look for synergies and also apply common rules to themselves with respect to their own accountability to the whole society. Again, the stewards can discipline purchasers and ensure that they contribute to one common system; that they consolidate the whole compact of institutional arrangements, and not just ‘their’ contract.

Data intelligence and learning: In Geneva, we thoroughly discussed the importance of a strong unified information system. Again, the stewards have an important role to play in this respect. In fact, the unification of the information system could be one of the best entry points for the stewards, both to advance the SP agenda and secure their own capacity to govern, regulate and enable. Beyond optimization of data, there is a broader need for leadership with an eye for collective intelligence. Today, in many countries, because of the fragmentation, no one has a good overview and no one encourages various purchasers to co-produce this overview. Actually, the observation of the very fragmented nature of financing in Francophone African countries, led CoP experts to investigate, in a second phase, how learning for UHC was taking place at country level. The subsequent study in six countries revealed that no country had a UHC learning agenda and most were quite weak on tasks required for SP.

Ways forward

SP will be key for making progress towards UHC. If we want to consolidate SP we can work on the following two fronts: at the level of (1) each purchaser, and at the level of (2) the stewards governing the whole health system. Here are a few things countries can do.

At purchaser level: Personally, I believe a lot in ‘learning by doing’. To really appreciate the power of SP, one has to practice it. So the first step a country should take is to kick off some real SP, even at the level of (just) one specific scheme.

In my opinion, one of the merits of Performance Based Financing consists in the fact that, for many countries, this was also the first SP experience. But there are probably other options – the introduction of a Social Health Insurance seems a nice opportunity as well for SP.

At the level of a specific scheme, our list of 4+1 sets of actions can also guide the consolidation of SP: the list helps to identify areas for improvement:. Use existing international evidence to update the package of services you pay for. Develop experience by contracting the public providers and then move to private-for-profit providers. Once your provider payment system is in place, update your contract to incentivize facilities to better address more challenging determinants of quality of care. Reduce the costs of verification with the adoption of risk-based verification. Consolidate learning loops in your whole program, as SP is a never ending improvement process.

At steward level: A lot can also be done at this level. I will highlight four aspects/actions, among many more.

First, let’s not forget that stewardship is a collective endeavor: each purchaser can, through active collaboration, contribute to better stewardship – ultimately, it will be about harmonizing mechanisms. Donors should acknowledge that they have been important creators of new schemes, programs. They should be much more committed to bringing coherence. It is sad to observe agencies – i.e. purchasers – that are reluctant to harmonize or even fighting each other (“my scheme is better than yours”), not recognizing that their own projects contribute to fragmentation.

A second possible area for action is data intelligence. In his presentation, Joe Kutzin framed the unification of information systems as a key step towards SP. This agenda seems less contentious. In Geneva, we heard that huge steps are already being set in this direction. We could even go one step further and build a national platform for knowledge sharing and collective learning (a recommendation which emerged from our multi-country study on learning systems for UHC).

A third possible action concerns the level of oversight. In each country, it would greatly help to have a governmental unit / taskforce / group in charge of coordinating all those in a position to act as a strategic purchaser – this will be particularly key for UHC. One of the key arguments for backing the CoP multi-country study was the realization that for all these countries, the existing “web” of schemes was the real starting point of their journey towards UHC. One should never forget that the cube is not empty: a mix (mess?) of schemes are already present in the cube!

A fourth area for action, the most difficult one, will be the merger of schemes. It is unclear what the ideal number of purchasers is (2). One could be tempted to answer one – for securing control over health facilities. Yet, such a monopsony also creates inefficiencies (an uncontested bureaucracy with no incentive to innovate at the level of the purchaser). Actually each market configuration creates its own problems – on this issue, I found the typology developed by Lorraine Hawkins really helpful.

Still, for sure, having too many purchasers in a country is not good. So streamlining schemes and eventually merging some should be on the agenda of the stewards of many countries. However, this is clearly not an easy endeavor: behind each scheme, there are strong and potentially reluctant stakeholders. In Geneva, we talked a lot about these political economy constraints. Path dependency matters – the choice made by many East European countries when they transitioned out of socialism, for a single (para-)public purchasing agency, was probably a wise one. In Geneva, we also heard about the important advocacy role for WHO.

For sure, SP is a long-term agenda. Things will progress slowly, at times, in an incremental way. But there will also be phases when SP is really speeding up. Our job is to find these highways.

Note:

In this study focusing on “schemes”, we didn’t count “aid projects operated by external actors” – which according to the definition we proposed in our first blog, are purchasers as well.

I do also believe that too many purchasers opting for SP could be an issue. Today, most NGOs provide their support in kind. I am not a great fan of support in kind, but in some situations (e.g. when the project has a short time span and delivers a modest contribution), it is probably a lesser evil than trying to radically transform institutional arrangements. Similarly, if each vertical program started its own Performance Based Financing, it would not help. Today, many of these actors do not radically question their input based model. But as time goes by and data becomes even more the pivotal resource of the health systems, more of them will probably be tempted to purchase more strategically. This will substantially increase the stakes at the level of the stewards of the health system.