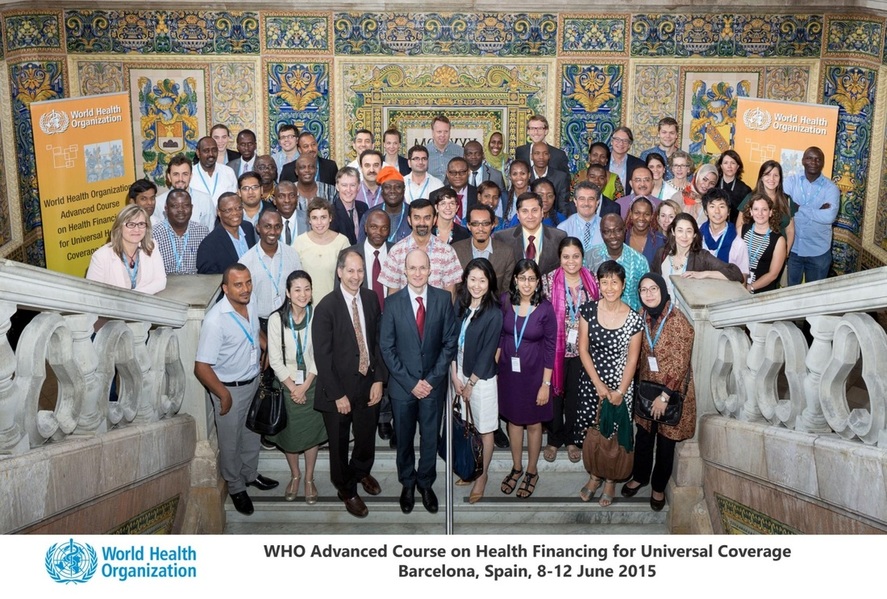

Kurfi Abubakar Muhammed (Principal Manager, Standards and Quality Assurance, Nigerian National Health Insurance Scheme) shares with us his feelings and experience after the course he attended a few weeks ago in Barcelona. This course is organised once a year. The next edition is foreseen around June 2016.

From 8 to 12 June 2015, I had the opportunity to attend the 2nd Advanced Course on Health Care Financing for UHC in low and middle income countries (LMICs) organized by WHO. The course is part of the WHO capacity building efforts aimed at developing the technical expertise of health care professionals working on health financing in LMICs. The 5-day program took place in Barcelona, Spain, with 55 participants working across 25 different countries. The main goal of the course is to bring participants to a common understanding of health financing and UHC; it also aims to share with the participants a common understanding of WHO’s health financing policy framework, and more generally, WHO’s approach to health policy. Empirical illustrations are also provided of how countries are doing in terms of the objectives of health financing policy for UHC, among others. There are plenty of LMICs in Africa, and many have not yet made much progress with respect to the attainment of UHC. Hence the relevance of this course to experts from countries like mine, Nigeria. We were not disappointed.

But first a few words on the setting. Even though I have never been a big fan of Barcelona’s football team, I have to admit I was excited to be visiting the town just 2 days after the team won the Champions League in Europe. Who knows, I could possibly catch up with all the celebrations? But besides the expectations of going to a Barcelona in a no doubt jubilant mood, one thing kept nagging at the back of my mind. Why choose Spain, of all places, to teach people from all over the world about health care financing or UHC? What lessons are there for LMICs from the land of Catalonia with respect to health care financing? I was therefore relieved when I heard upon arrival that the choice of the venue was more out of convenience and historical reasons rather than for any academic purpose [1].

Overview of the course

I found the course to be a comprehensive review of all the determinants of UHC in LMICs. Discussions related, among others, to fiscal space and the issue of sustainability tradeoffs - participants were made to further appreciate the concept of “fiscal space” and the key aspects of the macroeconomic and fiscal environment that will determine the potential government health resource envelope as it relates to financing healthcare. Another major issue that was discussed concerned revenue raising as it relates to financing healthcare; it highlighted the different categories of revenues, specific objectives for revenue raising policy, and the options available to policy makers. Linking revenue mobilization with pooling reforms in order to minimize risk in health insurance was also discussed; here we were made aware of why expanding risk pooling is an objective for UHC-oriented reforms; we also learnt to determine the desirable and undesirable features of pooling arrangements for the effectiveness of risk pooling (redistributive capacity). Then came the issue of strategic purchasing in health insurance which aims to show the challenges of allocation of pooled funds to providers for the delivery of services. We learnt to appreciate more the purchasing function and how it can be leveraged to achieve health system objectives. The pros and cons of the various payment options in health insurance were discussed as well as potential adverse incentives and unintended consequences of different provider payment systems and ways of combining different payment mechanisms.

Political economy of UHC

One of the main highlights of the course for me was the lecture on the political economy of universal health coverage by Rob Yates. In the lecture Rob emphasized the political dimension to the whole discussion on UHC, and how this relates to the economic and technical aspects of the debate towards UHC. Key lessons from the political economy concerns that have emerged and shaped how various nations have achieved UHC were shared, such as prioritization in the government budget for health, and how macroeconomic growth has been important in enabling countries to expand coverage and provide better financial protection for their citizens. Efficient allocation, reallocation as well as redistribution of scarce resources have also been shown to be effective strategies towards making more money available for health. What struck me, as a Nigerian, was how Thailand, a country with a similar GDP as ours, has been able to utilize removal of subsidies on fuel to finance health universal healthcare for its populace. Key to this however is strong political leadership with the capability to manage major social, political and economic changes towards mobilizing adequate resources to finance healthcare, and at the same time set up prudent and accountable expenditure management systems and policies that will ensure the expansion of coverage and provide benefits to the whole populace. I believe that the massive grass roots support for a new administration in Nigeria, the pedigree of the new president as someone whose word is his bond, and his knack for accountability and distaste for corruption can all serve as veritable templates upon which Nigeria can build its own foundation towards the attainment of UHC.

Reaching persons in the informal sector: re-thinking the policy options

It is well known that 70-80% of Nigerians pay for health care out of pocket. This absence of financial protection has tilted most Nigerians into poverty, due mainly to low insurance penetration, which is a measure of the relationship between premiums earned and the nation’s GDP, put at less than 6 percent. This gross inability of Nigeria as a country to provide health insurance to most of its citizens, especially those in the informal sector, at least till now, made me appreciate very much the lecture delivered by Joseph Kutzin of the WHO health financing unit. In the lecture he discussed the thorny issue of how to ensure that persons without regular salaried employment (the “informal sector”) are able to obtain the health services they need, with financial protection. He also showed how to apply a functional approach to a major health financing challenge, demonstrating the importance of this way of thinking and of taking a comprehensive view. Overall emphasis was on the value of re-framing the challenge away from “how do we get the informal sector to contribute” and towards “how do we ensure financial access and financial protection for everyone” irrespective of their employment status. As a firm believer and defender of Community Based Health Insurance as a path towards UHC, I began to see reasons why this may not be the best option for LMICs. Rather, for Nigeria to cover its informal sector with health insurance, it needs to devise more innovative financing options and block existing leakages in the management of finances in the country. In addition, health insurance needs to be made compulsory while utilizing the revenue from taxes, petroleum subsidies and other deductions to subsidize contributions for the poor.

The take-home message

The course was for me a very good opportunity to network with likeminded experts. I learnt a lot from my colleagues in Rwanda who struggle with the challenge of balancing population coverage and quality, or from my friends from Ghana who struggle to balance expenditure with income of the national health insurance scheme, and of course from experts in Indonesia whose reform to capture the middle class into the country’s UC health insurance is yielding fruits. Above all it was obvious to me and all other participants in the course that countries have reached UHC and that even more countries can and will reach UHC through different paths and trajectories. We agreed, though, that political commitment, community ownership, desire for social change as well as innovative financing options and efficient utilization of resources are all key to the attainment of UHC in countries.

Note:

[1] The “Casa Convalescència”, as the venue was called, is a magnificent cultural edifice of humanity that forms part of the complex of the "Hospital de la Santa Creu Sant Pau". It was designed in the late 19th century to alleviate the shortage of hospital space in Barcelona and was meant to serve as a relaxation center for recovering patients. It is now managed by the Universitat Autònoma of Barcelona as a center of academic excellence. The serenity of the place, the magnificent view, the quality of the resource persons, the nice and delicious meals as well as the hospitable nature of the people all contributed in no small way to the success of the training.