In this blog post, Bruno Meessen (Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp) reports on a recent conference organized by the Rotterdam Global Health Initiative and the Institute of Health Policy and Management (Erasmus University) in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. A nice opportunity to come back on the controversial topic of voluntary health insurance as a track to universal health coverage (UHC), it turns out.

For people working on UHC in Africa, there were at least two interesting events to follow (or even better, attend!) last week. In New York the first Global monitoring report on UHC was launched on Friday 12th with all bells and whistles; meanwhile, a more intimate symposium entitled “Strategies towards Universal Health Coverage: African Experiences“ took place on Thursday 11th at Erasmus University, Rotterdam. In this blog post, I will say a couple of things on the second event (without Tim Evans, but still with the likes of Eddy Van Doorslaer and Agnès Soucat, among others). The symposium marked the PhD graduation of Igna Bonfrer, a member of the PBF CoP (check here for a blog by her) - a promising start of a bright career, no doubt. Plenty of interesting things were said during the symposium. I will focus here on the morning program which was dedicated to health insurance. There were two presentations on voluntary health insurance schemes (VHI) in rural areas, a pilot government-led experience in 13 districts in Ethiopia and the Kwara State Health Insurance program initiated by the Health Insurance Fund in Kwara State, Nigeria, respectively; we also got some information on the current situation of the national health insurance in Ghana (where there’s quite an imbalance between revenue and expenditure, as you may know).

Can one learn something from recent voluntary health insurance schemes?

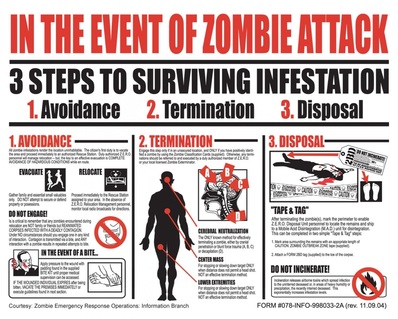

Over the last decade, several Dutch actors have been strong proponents of voluntary health insurance, also through private insurance companies, so Rotterdam was perhaps the right place to review this strategy. It is unclear to me how long this passion for VHI will last in the Netherlands, as it is at odds with growing evidence that there are real issues with VHI: they often only achieve low coverage, they are regressive (those who subscribe are not the poorest) and mark a fragmentation of the pooling. Joe Kutzin, for example, does not mince words about them : “VHI is like a zombie, shot many times, but always coming back”.

Nevertheless, zombie movies and other ‘Walking Dead’ series are in vogue again, for reasons not entirely clear to me. Could the same happen one day with VHI?

In Rotterdam, we heard evidence that the schemes in Ethiopia and Nigeria achieved rather good coverage rates (around 48% and 33% respectively, which is indeed more than decent), led to an increase in utilization and to a reduction of average out-of-pocket payment (50% and 70% respectively). So results seemed to be going against the - typically rather negative - reported VHI outcomes elsewhere. Let’s review them, in reverse order.

As for the out-of-pocket decreases, we have to qualify them a bit: they are largely due to the heavy subsidies to the schemes (which allow for instance not to request co-payment). Personally, I don’t really want to put emphasis on the out-of-pocket result: if the overall baseline situation is that households forego care, it could even be optimal for them, once they are entitled to the insurance package, to spend as much as they did before (as long as their higher consumption entails better health services).

The metric of utilization of quality health services seems much more important to me, given the pattern of dramatic underutilization we observe in most rural settings. So it is key that these schemes lead to higher utilization of (quality!) services. An important question is of course whether the increased utilization of the insured has positive or negative spillover effects for the non-insured. The two situations are possible, and I understood that there were different findings on this particular issue in the Kwara experience.

The coverage rate metric often receives a lot of attention. Obviously, if the enrolment rate is very low, you are not achieving a lot (as a participant told me during the break, you may even decide not to have a follow-up survey to measure the impact of your scheme which thus creates a bias for the global evidence base). A high coverage rate is certainly what countries are most proud of. Unfortunately, this indicates that people continue to misunderstand what UHC is: they wrongly equate UHC to the enrolment in a formal insurance scheme. As a reminder, if your country has a Beveridge system that is highly accessible to your people and tends to provide quality care, your coverage rate is probably not far from universal (ok, this is a rare configuration in low and middle-income countries, but it is possible).

Which coverage rate indicates success?

The question we debated in Rotterdam is whether a coverage rate of 40-50% could be already considered as a good result. By and large, participants agreed; more fundamentally, the conversation then focused on the idea that the policy momentum in your province or in your country is the key trend to watch.

After the bulk of disappointing experiences with VHI, we know that if you reach such high levels of coverage, it probably means that you got all the preconditions right, including that ‘something has happened at community and governmental level’. We learnt that in Kwara, the high enrollment (and the decision to scale up the scheme) owes a lot to the personal leadership developed by the governor of the province (a medical doctor, by chance). In Ethiopia, there is strong commitment from the State apparatus which, among other things, materializes into household coercion by the local authorities (as the latter are the fiduciary channels of a social assistance scheme for the poorest, they are able to deduct the premium for the VHI from the allowance).

Evidence that “something seems to be happening” is probably the real issue about UHC and one of the key dimensions we should try to capture in our monitoring efforts.

Ghana-France: 1-1

For instance, we can apply this lens of ‘something happening’ to a fourth metric sometimes used to assess a health insurance scheme: the balance between revenue and expenditure. When I listened to the presentation on Ghana which is facing huge problems with financing its national health insurance, I leaned over to the French expert sitting next to me and half-jokingly said, “hey, it looks like France!”. The vice-ambassador of Ghana, also present in the room, acknowledged that the country is facing a big challenge, but confirmed that the country would not stop its national health insurance – the momentum remains strong and the policy is very high on the agenda of different political parties. So, as Agnès Soucat put it nicely at the wrap-up session, the difficulties met by Ghana are probably more a sign of maturity and momentum than an indication of failure: progress towards UHC typically brings new problems, bigger problems (as they tend to be at a larger scale), and more visible problems; in short, UHC progress puts pressure on your governance system. Looking like France is a compliment!

The link between UHC and governance

It is clear we touched upon an important issue in Rotterdam: the bidirectional link between governance and UHC. For instance, the Ethiopian case sparked a discussion on the fact that several VHI/CBHI schemes are in fact mandatory schemes. The need to make subscription compulsory seems to provide a premium to authoritarian states with a strong administrative apparatus.(1) But one could also argue, instead, that this premium is short term, as UHC is fundamentally about societal cohesion. To some extent, this echoes the question of the best developmental model: the Chinese one (one ruling party with strong economic growth) or the Indian one (a strong democracy with lower economic growth)? Important governance and development questions like these will never be far away as the UHC agenda is to be implemented in the coming years. And from this perspective, the high coverage rate achieved in Kwara could indeed be a major achievement, as Nigeria is probably less receptive to coercion (however, this is not saying much yet about the scalability of the strategy).

The more I interact with countries’ decision makers and other domestic stakeholders (mainly through the communities of practice nowadays), the more I believe that the current dominant international approach to UHC is far too technical. UHC can and should certainly be measured against some clear objectives, so we need reports like the one presented in New York last Friday. But they won’t suffice.

UHC will be a long journey and the process will be key. Of course, you must head in the right direction from the start, and you should be aware of path dependency. The key, however, is to kickstart the momentum and maintain it. If your ‘UHC system’ is in a learning mode (we will come back on this point later this year), and if your citizens reckon that UHC is a core component of the nation, like seems to be the case in Ghana now, you are most probably on the right track.

Note:

(1) Interestingly enough, China, Rwanda and the regional authorities involved in the Ethiopian pilot have all three (1) introduced performance indicators to measure the performance of their local administrative authorities and (2) incorporated the ‘insurance enrolment rate’ as one of the indicators for this yardstick evaluation.