Ten years after the WHO’s report on Universal Health Coverage (UHC), most African low- and lower-middle income countries are not able to raise enough resources to achieve UHC. And however important, domestic efforts for resource mobilisation alone will not be enough to bring us there. The world has a collective responsibility to address tax injustices and high indebtedness, which have a huge potential to free resources for health.

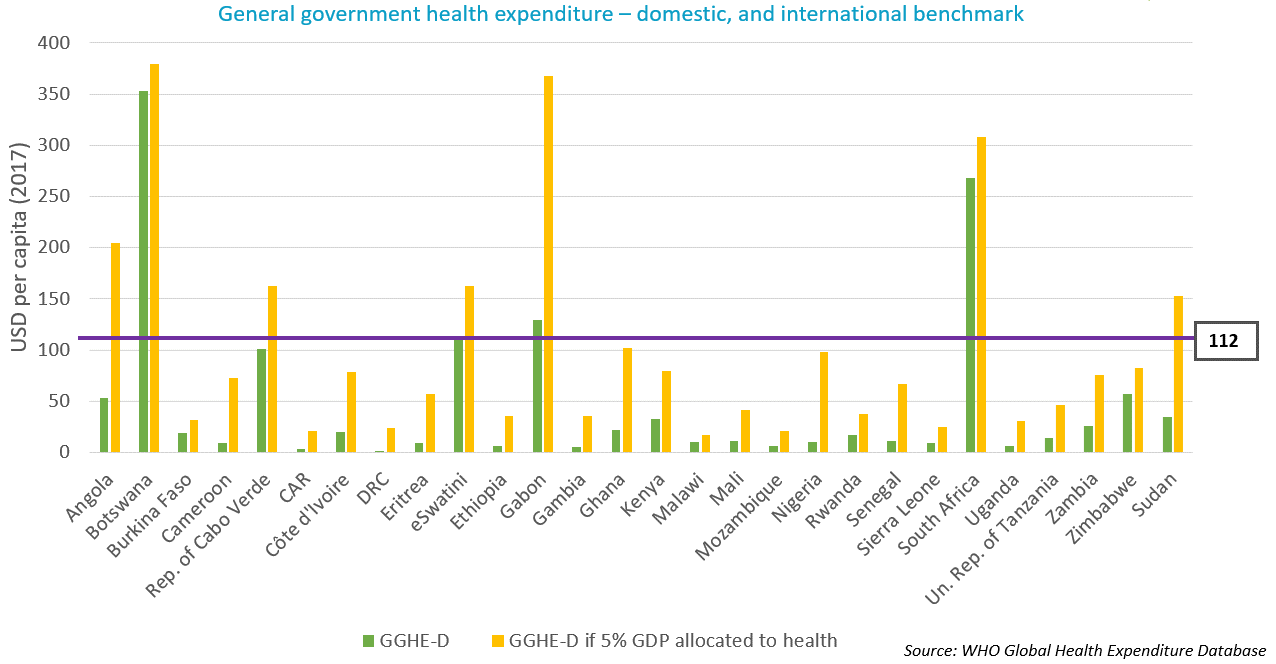

While in the last ten years we have witnessed improvements in several health indicators, poverty and inequality remain core challenges. People living in poverty suffer many more health problems, have far less access to quality health services and, still, many people are driven into poverty each year because of health expenditures. An important step for many governments to take towards UHC is to not only redistribute but also raise more revenue to cater to their population’s health needs. The global community increasingly emphasises governments’ responsibility for domestic resource mobilisation for health. However, most low- and lower-middle income countries (LMICs) in Africa are not raising, and in the short to medium term, will not be able to raise, enough domestic resources to achieve UHC. They remain far from achieving the twin health spending targets of at least USD 112 per capita per year and 5% of GDP. The reality is that even if they manage to allocate 5% of their GDP to health this amount will still be far from enough (figure 1). External sources will continue to be critically important for many LMICs health spending in the medium term.

The prospects for economic growth are not good for many of them and, in fact, many people are left behind by economic growth - as expressed and measured by countries’ GDP. GDP increases do not automatically translate to poverty reduction nor to increases in the countries’ health spending. Especially so when pathways towards economic growth do not pay sufficient attention to equal distribution of wealth and investing in social sectors, which has been the case for many years under the influence of policy advise or conditions put in place by the IMF and the World Bank. This has been the dominating directive and trend at least for the past couple of decades, while the achievement of equity and investment in UHC requires different approaches. The Covid-19 emergency has moved the dial towards more flexibility and introspection within these institutions, at least in their rhetoric. As recent findings from Eurodad, Oxfam and ActionAid demonstrate, practise is not following suit.

Even if economic growth accelerates considerably in the near future, domestic resource mobilisation alone will not be enough to realise SDG3 and UHC by 2030. To achieve the health-related SDGs, LMICs require an additional USD 371 billion per year. Furthermore, the annual funding gap would remain at USD 54 billion even with projected increases in their domestic health spending. Given these caveats, which are the leading strategies to increase a country’s fiscal space for health? The WHO and international financing institutions like the IMF are flagging three: 1) earmarked taxes, 2) reprioritisation of health in government budgets, and 3) public financial management (PFM) reforms and efficiency improvements.

1. Earmarked taxes for health, aka 'sin taxes', is a commonly suggested solution for raising resources, initially introduced though to reduce consumption of harmful products. However, the WHO’s own research has shown that sin taxes have a very limited potential in raising resources for health, they are not predictable, and they do not have the prospect of leading to sustained, long-term expansion in fiscal space for health.

2. Reprioritisation of health in government budgets is important but will bring limited amounts of resources in many LMICs due to the already constrained public purse.

3. As for the gains from PFM reforms and efficiency improvements, despite high potential, they will take time to materialise and still won’t come close to filling the massive funding gap.

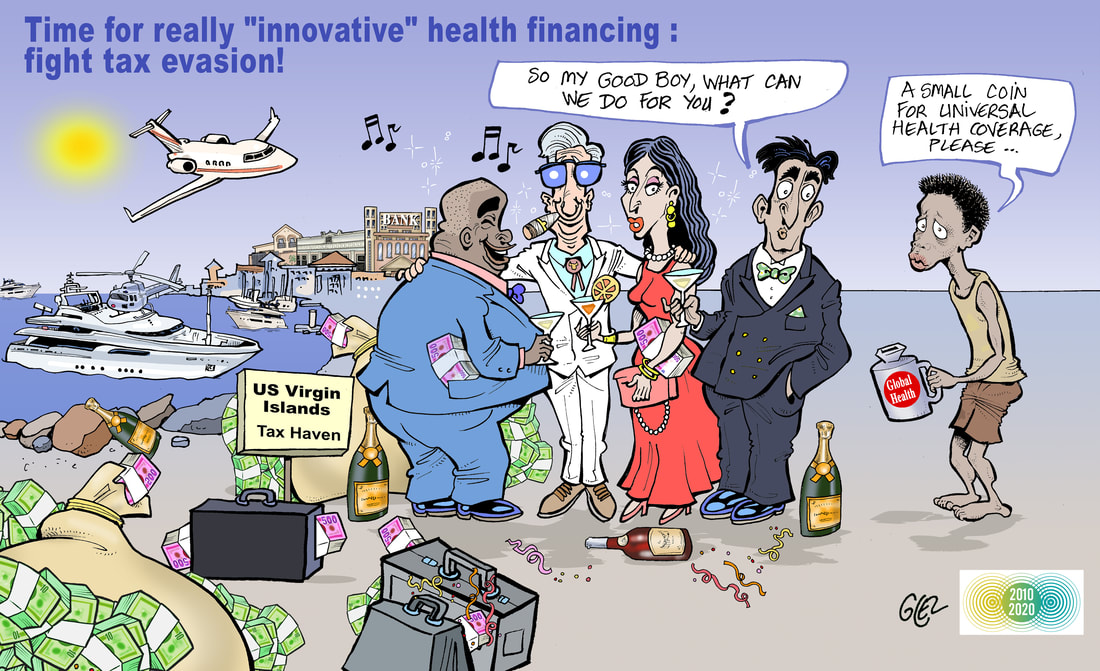

It is clear that the world needs alternative avenues to expand fiscal space in LMICs and allow for higher investments in the SDGs, including health. This is something for which organisations like the ILO and UN Women, among others, advocate. The alternatives are not new. They are just not yet actively explored because they challenge mainstream political and macroeconomic thinking. The latest UNCTAD report estimated that Africa is losing USD 89 billion per year in illicit financial flows such as tax evasion and theft, which amounts to more than it receives in development aid. The potential of this untapped source of revenue is clear when compared with the annual funding gap for the health-related SDGs previously mentioned. At the same time, debt service repayment on average takes over almost 12% of African governments’ revenue, while the average domestic allocation to health is half of this.

To conclude, health, as well as other social goals, need far more public resources. Mainstream approaches to economic growth are not leading to higher well-being, equality and realisation of the SDGs. To meet the SDG3 targets, including UHC, a rethink is needed on how to get there, putting equity centre stage and challenging mainstream thinking on economics and finance.

*The authors are global health advocates from Wemos’ health financing team. Wemos is an independent civil-society organisation seeking to improve public health worldwide. It analyses Dutch, European and global policies that affect health and proposes changes in them. Wemos holds the Dutch government, the European Union, and multilateral organisations accountable for their responsibility for respecting, protecting and fulfilling the right to health.