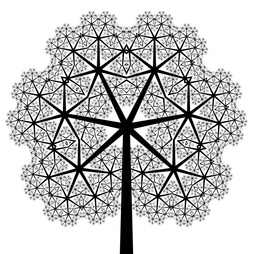

Figure 1. New organizational system for CoPs (on a fractal design)

Figure 1. New organizational system for CoPs (on a fractal design) The new ambition of the CoPs is to increase opportunities for the CoP experts, through the launch of different collaborative projects. However, to make this transition possible we also need to reorganize our facilitation structure. In this blog, we present you the model towards which we are heading. If you have been with us for some time already in our CoP, there might very well be a new role for you!

The limits of the current model

In a recent blog, Bruno reviewed the five years of existence of the CoP Performance Based Financing (CoP PBF). He mentioned among other things how he has become sort of a bottle neck himself as a key instigator and focal point of PBF CoP activities. In recent years, we have tested models with better equipped facilitation teams. The Financial Access to Health Services CoP (CoP FAHS) went furthest in implementing this model. In the end, however, this approach did not lead to the expansion we expected to get.

In Rabat, we discussed this model of organization. For the PBF, FAHS and Health Services Delivery CoPs, the diagnosis was clear: so many of our beautiful projects have been put on hold due to our non-availability. We see the future in the model that was launched last year during the « Results Based Financing & Information Communication and Technology » workshop that was led by an autonomous central facilitation team.

The new model

To get rid of the bottle neck of facilitators, our new strategy will involve an organigram of facilitation that allows delegation of more responsibilities (the word « organigram » is not very appropriate as CoPs are not conventional organizations with a hierarchy and employees, but we could not find a better word for the time being). We are going to move away from our flat “rake” organigram towards a more decentralized organigram (see figure 1).

In practice, from now on, each activity of the CoP will be conceived as a collaborative project. This project will be assigned to a “project manager” (by the way, we find the term « project manager » not very original, and we will reward anybody among you who comes up with a better one with a PBF T-shirt – just offer your suggestions as comments to this blog). The main responsibility of the “project manager” will be to see the project through, from start to finish. These new project manager posts will be new opportunities for our more experienced and motivated experts. They can show their passion for knowledge management and their will to help the more junior experts to grow (in terms of knowledge, competences, …).

The selection of « project managers » will take into account the nature of the projects. In fact, as you’ll gradually discover as the collaborative projects will be shared online in the coming weeks and months, these projects will be of a different nature. Some will be relatively short, others will last for quite some time. Some will be small projects, others will be much heavier. Some projects will require both English and French, others not. Also, some will be more technical, others less. The title of “Project manager” will thus be confined in terms of content and time. You should note that the expert who will have accepted this responsibility will have in advance agreed to precise terms of reference. He or she will also undergo an evaluation of his/her own performance (by his/her colleagues experts involved in the project).

Implementation

This model will be gradually implemented. The speed will depend, among other things, on the volume of collaborative projects that we will be able to launch. Obviously, it is possible that all will not work smoothly from the beginning, but the most important is to start embracing this transition and take a decisive move forward, towards this new CoP development. We count on your support to succeed in this new model of facilitating CoPS.

Translation: Seleus Sibomana