Last year, a Working Group on corruption in health services in Africa was created on Collectivity. After a first blog by Juliette Alenda on the challenges of defining petty corruption, we present here the results of the second strand of our activity: an empirical analysis covering more than thirty African countries.

| The issue of informal payments in the relationships between patients and health staff remains little studied/documented in African countries, whether from the perspective of petty corruption (emphasis on illegality) or undue user fees (emphasis on informality). Beyond the diversity of definitions and approaches found in the literature (see the previous blog), the limited data available on this phenomenon, shows that it is a real scourge in several countries. The existence of informal payments (we will use this expression rather than petty corruption in this blog post) is not only an additional financial barrier to accessing care for the poorest in particular, it is also an added problem on top of the many other dysfunctions that characterize the health systems of several low- and middle-income countries. |

The objective of this brief study is to lift the veil on certain aspects of informal payments by mobilizing databases that are freely accessible to the public, in order to put a figure on this intrinsically diffuse phenomenon. The goal is to create an interest in taking this issue into account, among all the actors involved in improving the performance of our health systems.

1. Level and evolution of informal payments in public hospitals and health centres in Africa

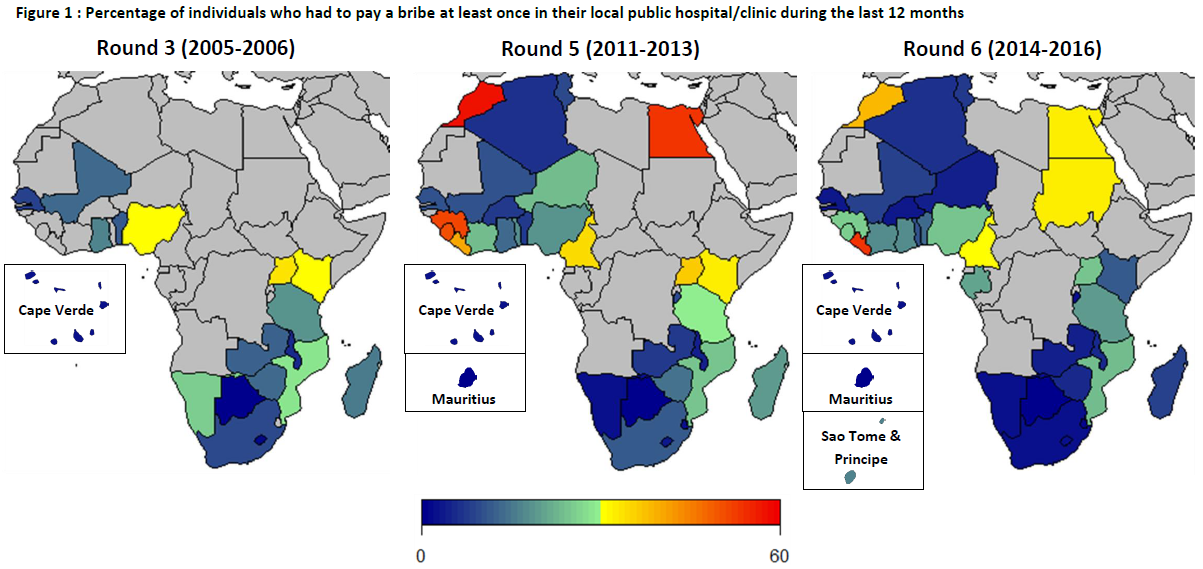

A picture of the situation in 2005-2006, 2011-2013 and 2014-2016 as presented in Figure 1 highlights various profiles for African countries with regards to the extent of the phenomenon. In countries like Botswana and Mauritius, it is almost non-existent, while it is a real problem in Cameroon, Egypt, Guinea, Liberia, Morocco, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Uganda for example. Looking at the evolution over time, there is a general downward trend between round 5 (2011-2013) and round 6 (2014-2016), with the exception of a few countries (Algeria, Benin, Ghana, Liberia, Malawi and Nigeria). It is also important to note that between these two rounds of surveys, the percentage of individuals who reported having to pay bribes to access care in the public sector has been halved or more than halved in one-third of the countries (Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cape Verde, Guinea, Kenya, Madagascar, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe). However, the scale of the problem remains worrying in about 10 countries where more than 20% of those interviewed had to pay informal payments in public health facilities.

This diversity of profiles and trajectories between countries probably reflects their contextual and structural differences (different general climate of corruption, differentiated development/implementation of health insurance or free care policies, disparities in the level of public expenditure on health, etc.) that would be interesting to study, whether from the point of view of research or evaluation of public policies.

2. Links with other failures in health care provision

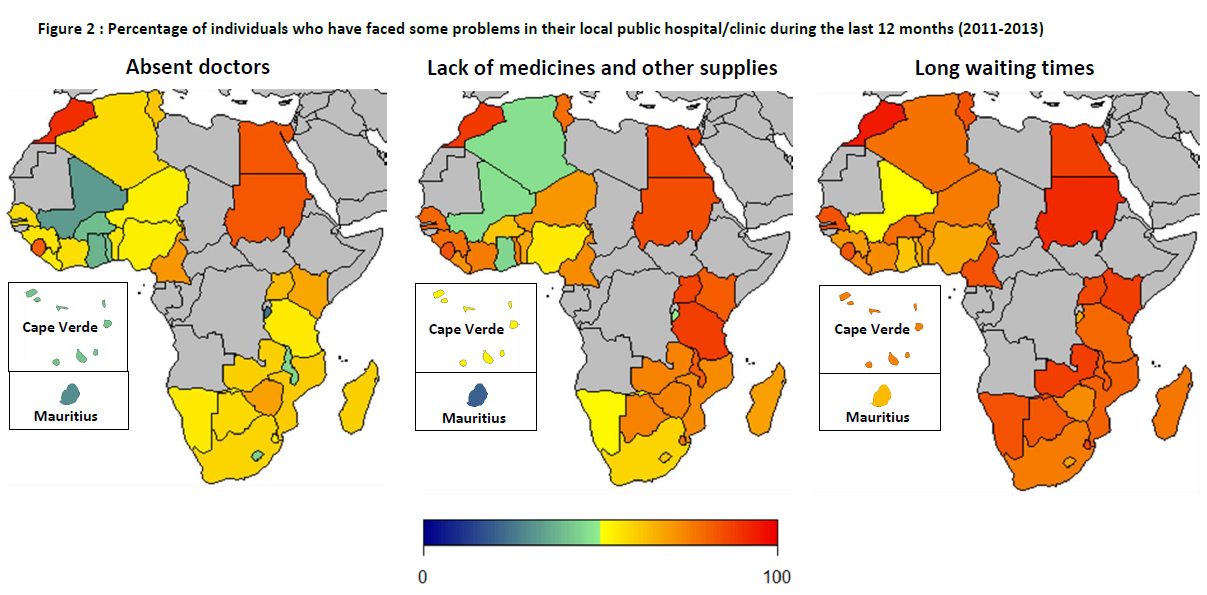

In round 5 of the Afrobarometer surveys (2011-2013), people were also interviewed about the other problems they faced in public health facilities. The data presented in Figure 2 shows that in 25 out of the 34 countries covered, more than half of the citizens reported having faced absenteeism of doctors in their public hospital or health centre. The percentage varies from 23.3% in Burundi to 90.4% in Morocco. As for stock-outs of medicines and other medical supplies, apart from Mauritius where only 20.2% of interviewees reported having faced this problem, in all other countries it was very recurrent (between 44.5% in Ghana and 88.9% in Morocco). The problem of long waiting times in public health facilities was even more frequent, with more than 6 out of 10 people reporting having faced this difficulty at least once in the past year in all countries (from 61.1% in Ghana to 94.7% in Morocco), except Mali (51%). Finally, issues such as a lack of attention or respect from health staff (from 34.5% in Mali to 90.6% in Morocco) and dirty hospitals and health centres (15 2% in Cape Verde and 90.2% in Morocco) are also worrying.

A previous study (1) (at the individual level) has shown that people who report having faced these dysfunctions (absent doctors, drug stock outs and long waiting times) in public health facilities were also more likely to report having had to pay bribes.

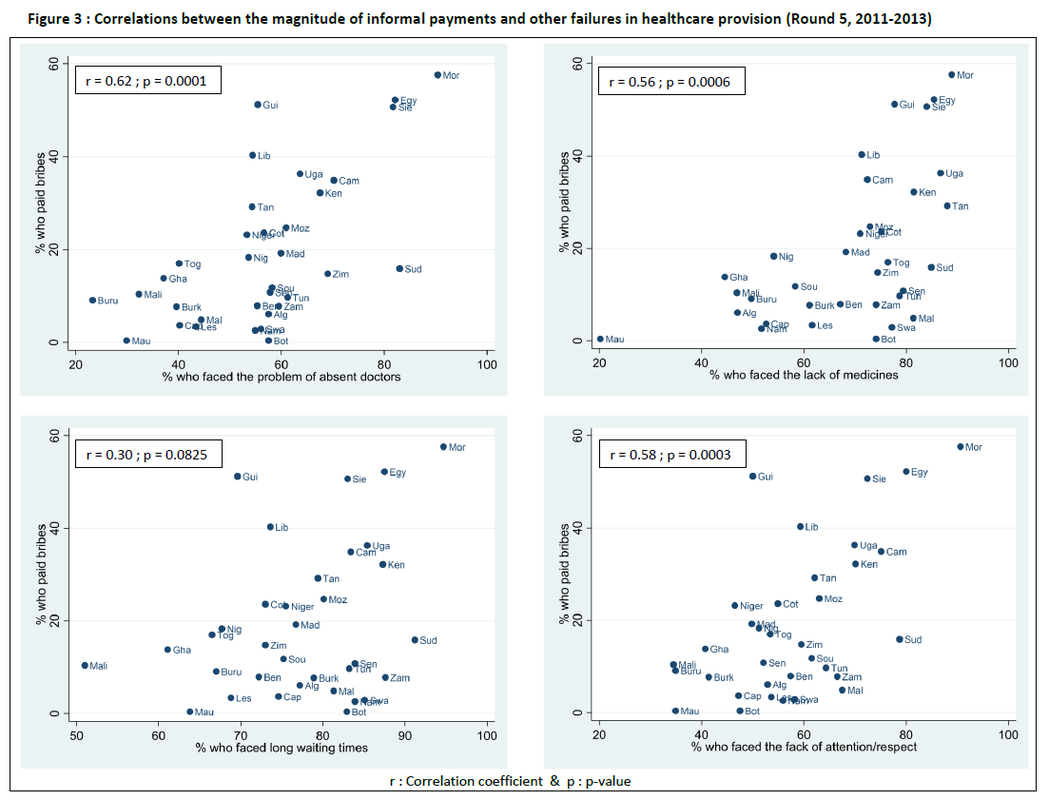

Similar patterns emerge when the data is aggregated at the national level. Indeed, Figure 3 shows that countries with high proportions of individuals reporting having paid bribes in public hospitals and health centres are also those where:

- high proportions of individuals report having faced doctors’ absenteeism (r = 0.62, p-value = 0.0001);

- high proportions of individuals report having faced stock outs of drugs and other medical supplies (r = 0.56, p-value = 0.0006);

- high proportions of individuals report having experienced long waiting times (r = 0.30, p-value = 0.0825);

- high proportions of individuals report having faced lack of attention/respect from medical staff (r = 0.58, p-value = 0.0003);

- high proportions of individuals report having faced insalubrity in these health facilities (r = 0.61, p-value = 0.0001).

These stylized facts can be interpreted in two ways: (i) the existence of informal payments is just one of the many health systems failures or (ii) it is a consequence of these dysfunctions. The first explanation, that of simple correlation, would reflect the fact that the coexistence of informal payments and other problems like doctors’ absenteeism or stock-outs of drugs are jointly determined by other factors that are internal or external to health systems (e.g. chronic underfunding of health facilities). The second interpretation is more frequent in the (economic) literature and refers to the fact that informal payments arise from the existence of other problems. Here, the explanation is that actual or fictitious shortages of human and material resources (in face of patient needs) create incentives for patients to pay more for the services they are seeking, including paying informally. A scarcity of quality services leads to an increase in prices. Based on the failures of health systems (shortages being their main manifestation) in some Eastern and Central European countries after the communist era, Gaal and MacKee (2004) have developed a theory - INXIT - around this explanation (2). For them, informal payments are a behavioural reaction to these difficulties, especially when the channels of EXIT (i.e. the existence of alternatives) and VOICE (i.e. the possibility to protest) are blocked. Moreover, in a qualitative study conducted in Tanzania, Maestad and Mwisongo (2011) found that informal payments were the result of rent-seeking activities of health workers who create artificial shortages or voluntarily reduce the quality of care provided to patients to nudge them to make additional payments (3).

In conclusion, the data from Afrobarometer surveys highlight various profiles and evolutions of some 30 African countries with regard to the issue of informal payments in public health facilities. The data also shows a worrying situation in all of these countries, particularly when dysfunctions such as doctors’ absenteeism, stock-outs of drugs, long waiting times, lack of attention/lack of respect from health staff, and insalubrity in public hospitals and health centres are examined. Basic bivariate analyses show strong correlations - at the national level - between the extent of these dysfunctions in health care provision and the magnitude of informal payments. While it is not possible to conclude on the existence of a causal relationship, elements from the existing literature on the topic strongly suggest this possibility. This question deserves further investigation to better understand the underlying causes of the existence of informal payments in the health sector, and to design and implement effective measures to reduce their magnitude and impact on access to health care for the poorest populations.

The Working Group on corruption in health services in Africa takes this opportunity to invite readers who have comments, suggestions or explanations about a particular country or group of countries to come forward. As the individual data from Afrobarometer surveys are available, we would like to explore ideas of further analyses that could be generated by this work. Likewise, we welcome any information on other existing databases that would make it possible to study this phenomenon in one way or another in the context of African countries.

(2) Gaal P, McKee M. Informal payment for health care and the theory of ‘INXIT’. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage, 19 (2004), pp. 163-178

(3) Maestad O, Mwisongo A. Informal payments and the quality of health care: Mechanisms revealed by Tanzanian health workers. Health Pol. 99 (2011), pp. 107-115