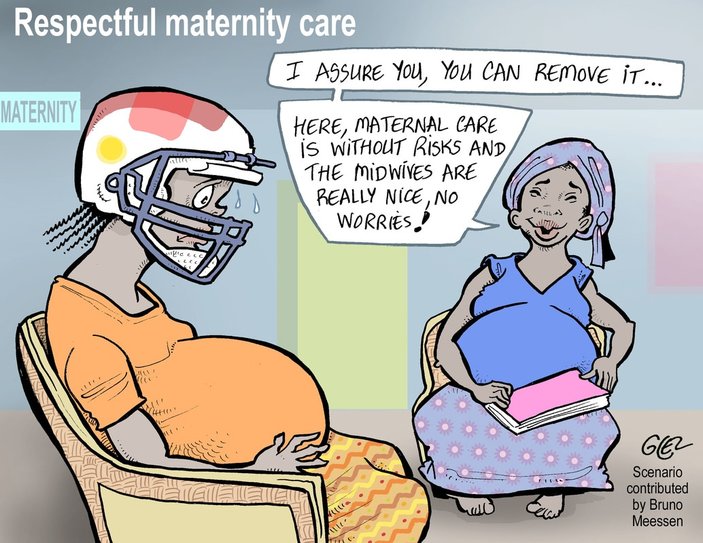

Respectful Maternity Care: status of the knowledge

Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) can be defined as the provision of dignified care to women. In recent years, the topic has featured prominently in maternal health, public health and human rights research. Literature reviews in 2010 and 2015 delineated what disrespectful care looks like. A 2016 review examined what drives disrespect in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and several studies (including Abuya 2015 and Sando 2016) have examined the prevalence of disrespectful care during childbirth. While knowledge of the problem is extensive, insights into a solution remain limited and narrow in scope. With one notable exception, studies detailing comprehensive, system-wide solutions are nearly non-existent.

| Within the Performance Based Financing (PBF) community, RMC has scarcely gathered attention. A 2017 review on quality of care in PBF programming has noted that, to date, quality indicators have been focused on equipment and infrastructure with far less attention paid to patient-provider interactions or client perceptions of care, although these latter facets are emphasized in the WHO’s 2015 “Vision of quality for pregnant women and newborns”. We see the challenge of RMC as an opportunity for PBF, and we urge colleagues within the CoP to consider how an output-based approach might address dilemmas related to disrespectful care. The RMC community has built a compendium of indicators that could be used to measure disrespectful or abusive care. A sampling of questions (and their broader domains) that capture facets of disrespectful care, and could be incorporated into patient surveys and patient-provider observations are presented in Box 1. We urge the PBF community to consider whether or how indicators like these could be integrated into | BOX 1 - A sampling of indicators* (and their broader domains) that could be used to measure Respectful Maternity Care

*Source: https://www.k4health.org/toolkits/rmc/indicators-compendium |

Findings from our two evaluations

In terms of documenting the problem of disrespect, our findings reflect existing RMC literature. Across evaluations, women and community leaders described overcrowding and strained or cursory patient-provider interactions that often entailed demeaning, discriminatory or harsh remarks on behalf of providers.

In both evaluations, respondents reported feeling that providers were tired or overworked, and that they looked down upon the clients they served. The RBF4MNH evaluation placed particular emphasis on maternal care during delivery. In that study, women described how providers did not explain or effectively communicate what they were doing during labor and delivery. Women said they felt ignored. In extreme cases, women described giving birth alone or in the presence of an unskilled companion such as a friend, family member, fellow laboring woman, cleaner or security guard; in three instances, women described how their newborns fell to the floor during delivery as nobody was present to catch their baby. For their part, providers described feeling overworked and undervalued.

In terms of solutions, our evaluations also uncovered reasons to feel hopeful. After three years of implementation, respondents in both evaluations described facilities as having more equipment and better infrastructure (including, in the case of RBF4MNH, enhanced visual privacy via screens); being cleaner; and having a more consistent flow of supplies. Women who sought care in RBF4MNH intervention facilities were more likely to report satisfaction with the level of confidentiality and privacy provided to them during labor and delivery than their counterparts in control facilities. Finally, in both PBF programs, respondents described sensing that the program’s inclusion of patient feedback enhanced provider accountability. In RBF4MNH, this took the form of exit interviews wherein clients were asked a series of questions regarding their encounter with providers. In SSDI-PBI, this took the form of meetings where community members and providers could air grievances and discuss solutions. Whether through exit interviews or collective forums, the process of sharing insights and solutions forced health facility staff to recognize that a patient’s experience of care matters. As one provider said, “Look, when you know you are in part being assessed based on what a woman says, you have to be nice.”

Could PBF contribute more to respectful care?

We have debated within our research team whether it may be feasible for future PBF programs to more pointedly address mistreatment, by incorporating indicators that emphasize respectful care into quantity or quality checklists. We have also posed the following question to providers ‘Could an incentive scheme that rewards respectful care spark lasting changes in provider behaviors and attitudes?’ to which providers responded with caution. Several providers noted that within any given facility there is often a “bad apple” who tarnishes the image of the facility and seems obstinate in their disrespectful approach. Other providers described how a change in incentives could lead to workarounds that don’t eliminate disrespect, but merely shift the role of who is undertaking the disrespectful behavior. For example, overstretched facility staff could recruit those who accompany women to facilities-- in-laws, sisters or mothers --to enact verbally or physically abusive behaviors toward an “uncooperative” laboring woman. We envision that there are many more unintended consequences that could erode trust even amid a well-intentioned, respectful care-focused PBF program.

Despite these challenges, we err on the side of optimism. We recognize that the current dearth of interventions addressing respect is likely linked to the fact that this problem is multi-faceted, emotionally-charged, politically sensitive, and it transcends several tiers of the health system while also demanding long-term, cross-sector collaboration. This makes promoting respect a daunting prospect, but such challenges are not new to those working within PBF.

In fact, we see several parallels between the essential ingredients of a RMC-focused program and the historical experiences of PBF programs. Do both PBF and RMC programs demand a seismic shift in the way a health system operates and views itself? Yes. Do both PBF and RMC efforts require stakeholders from across ministries and sectors to work together in heretofore unheard of ways? Yes. Are PBF and respectful care programs likely to be perceived as burdensome or problematic by providers? Yes. Is the PBF community accustomed to questions and critiques regarding sustainability and cost – perhaps more than any other health intervention in recent memory? Yes it is, and the RMC community may need to brace for this too. Finally, must both PBF and RMC programmers consider how to bring about changes that ripple through several target audiences including: individual clients, households, communities, facilities, district health management teams and multiple ministries? Yes, they do. Given these parallels, could the PBF community harness their tacit and explicit knowledge and devise novel ways to address mistreatment of women? We think so.

*The researchers are engaged in evaluations of the RBF4MNH program and the SSDI-PBI program in Malawi. These evaluations were sponsored by donors including: the governments of the United States and Norway through the USAID | TRAction Project at URC, the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Malawi, and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad).