More than 100 practitioners, policy makers and researchers from the Africa region came together in Dar es Salaam to share insights on performance based financing. Sophie Witter from the ReBUILD consortium reflects on her take-home observations from the three-day meeting, convened by ReSYST consortium and our PBF Community of Practice.

Challenge 1: managing maturity. PBF programmes have been being piloted and rolled out across the developing world at a rapid rate over the past decade. We are now entering a new phase where some schemes are reaching maturity and facing new challenges – how to stop indicators from plateauing, how to continue to innovate within a model which is now well established, and how to maintain support and momentum. In Burundi, for example, one of the few countries which has scaled up nationally with PBF, Eric Bigirimana described the challenges of cost escalation, of integration with new reforms, and of shifting political priorities.

Challenge 2: moving from volume to quality. Although PBF programmes have mostly had a quality component already, the main focus is now shifting towards quality, rather than volume of services. This opens up new operational and research challenges, but can be achieved. The PBF programme in Zanzibar, which focuses on quality, has apparently shown early promise in reducing unnecessary antibiotics and increasing adherence to protocols, for example.

Challenge 3: coping with scaling up and out. The early adopters of PBF benefited from close attention and support from NGOs, consultants and donors. Inevitably, as programmes go to scale and expand, they start to face some of the real-world messiness of implementation in sometimes less favourable contexts. One presentation from Benin, for example, highlighted the limited use of PBF data, the lack of feedback to communities, and the high costs of verification. This is not how PBF is meant to work, but is all too familiar to people who have studied policy implementation processes. Implementation is not easy, even in the best environments. The quality checklist alone has 400 items in Benin. No wonder that verification costs 54% of the total PBF expenditure. More work will be needed to reduce costs (for example, through better use of technology) but also streamline processes and increase real accountability to communities.

Challenge 4: sustainability and beyond. A range of preconditions for sustainability are apparent from the early case studies, especially Rwanda, where the Ministry of Finance was brought on board, including through a pilot which showed that public financial management systems could be adapted. The process of decentralisation, including management of staff, was another key enabler. In Rwanda health facility management are able to planning and managing their overall resources. How PBF will be integrated in overall funding streams and wider health policies is however still up for debate in most contexts. What is the end point? Will it fuse with health insurance? There has to be a forward vision – evidence from countries where PBF has stopped highlight the risks of starting and stopping in an incoherent way.

It is really encouraging to see the growing maturity not only of PBF but also the research community working on it, some of whom came together in Dar es Salaam. Four research themes and challenges were also highlighted.

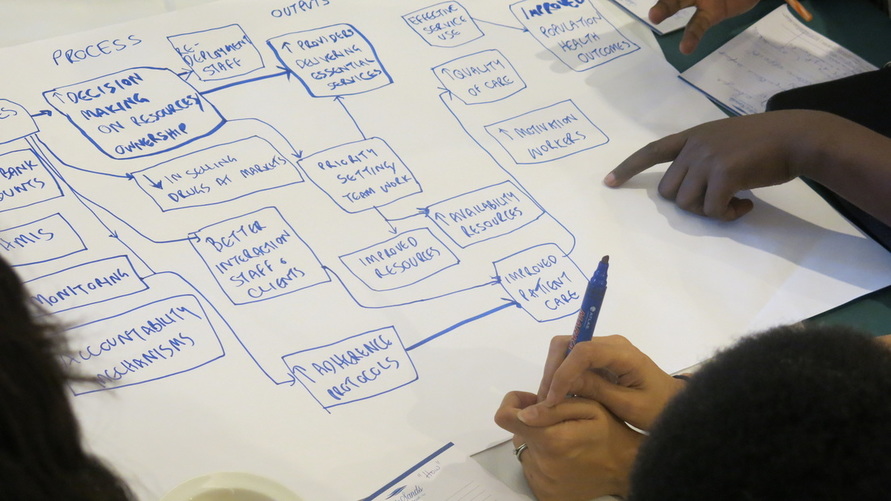

Research challenge 1: making more explicit the theory of change: There is a continuing debate over the mechanisms through which PBF may work. Is PBF’s main significance in adding funds (providing a new channel, one with particular appeal for donors), in changing incentives, in changing and clarifying roles, in increasing autonomy over resources, or in simply giving some much needed feedback to staff and managers labouring in the public sector? (Certainly some of the emerging research evidence points to the importance of supervision and feedback to staff as a key motivator). Or is the PBF the ‘glue’ which holds the other elements together (helps to make them happen)? What are the levers at systems, district, facility and health worker level? While theories of change have being developed, there is still much debate on the relative importance of the different components (knowledge of which could improve the cost-effectiveness of the PBF).

Research challenge 2: Unpacking motivation: One of the main mechanisms which is implied by PBF is the increased motivation of staff, and new studies are now emerging which examine this. Does PBF crowd out or in intrinsic motivation, for example? Emerging findings from Afghanistan and Tanzania suggest no impact on motivation, which is surprising but also intriguing. Either we are not measuring it well or we are misunderstanding how PBF works (both of which create interesting challenges). In Afghanistan, for example, facility functionality was found to be a key factor for quality of care, not motivation, which did not shift. Researchers shared views on how to develop better tools and understanding of how (and whether) to measure this concept. It was recognised that motivation is complex and that the relationship between it and performance is also not verified.

Research challenge 3: knowing more about the know-do gap: Recently, studies focusing on the know-do gap of health staff – and how this is affected by PBF – have grown. One study in Tanzania found that the gap had increased – because knowledge had increased while practice did not change. Another, from Burundi, found that the know-do gap was small, but mainly because knowledge was low. (The score was 28% score for consultations and 37% for vignettes, so pretty low overall, suggesting that PBF alone cannot raise the quality of care). More thinking is also needed about this tool; the gap is usually interpreted as indicating lack of effort, but of course it may be the result of lack of drugs, equipment, other environmental factors or even the pressure of targets.

Research challenge 4: moving to meso: While increasing attention has been paid to the health worker level, not enough is being done to understand the impact of PBF on organisations – for example, how it is or is not changing team dynamics, social norms, and supportive practices. These are critical to behaviour change, but have been neglected, partly because of the disciplinary make-up of the field (too many economists…).

In short, there has been plenty of progress but also a lot of food for thought, and for improved action.