We continue our exploration of community participation in Africa, 25 years after the Bamako Initiative. Dr. Frederick Golooba-Mutebi is a political scientist and Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the School of Environment and Development, University of Manchester and Research Associate of the Africa Power and Politics Programme at the Overseas Development Institute in London. He has widely published on health, local government and other topics, with a concentration on Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan and South Africa.

Jean-Benoît Falisse: You have been working on issues of community participation for quite a few years now. What sparked off your interest for this topic?

Fred Golooba-Mutebi: My interest stemmed from the knowledge I had of how the society I was born in works. I had grown up in it and knew roughly how people felt and thought about different things. A key aspect of participation is that it presumes that communities, wherever they are found, always want to assert themselves over their leaders or people in positions of power and authority. My own society is very hierarchical in orientation. People generally treat leaders with deference. And even if one does not respect a leader or has an issue against him or her, they are more likely to avoid than confront them. The idea of participation with people holding their leaders to account is therefore a difficult proposition. Traditionally local leaders did not account directly to the community. They accounted to their superiors, the senior chiefs, and ultimately to the king. In distant (pre-colonial) times, before the region I was born in became more populated, people could easily move house from one area to another one. The possibility of shifting enabled them to vacate areas presided over by leaders they did not like to those with leaders who had a reputation for being good. The consequences for a leader whose people “voted with their feet” included being deposed by the king. In short, my knowledge of my own society conflicted with the theory of popular participation. That triggered an interest in me to go and investigate the extent to which it was feasible. I found that it really is not. Like it or not, traditions and ways of seeing or doing things live very long.

Community participation was a key principle of the Bamako Initiative. Today is seems the Bamako Initiative hasn't quite reached its objectives. What do you think are the main reasons?

There are several reasons. One is that service delivery in health care fails because of factors that go way beyond what participation can address or rectify such as the availability of medicines and human resources in rural areas and the professional supervision necessary for delivering care according to established standards. The idea of wanting to ‘capture’ for the public sector money people were spending on private provision was a good one. However, its weakness lay in assuming that people would be as willing to pay for care in government facilities as they were in private ones. Experience in Uganda has shown that it certainly wasn’t the case. For many poor people, paying for care in government facilities alongside paying taxes was a contradiction in terms. “Why pay taxes and then pay for services as well?’ People knew that owners of private facilities were ‘doing business’ and therefore had to make a profit but the idea that government facilities should do the same clashed with many people’s understanding of what governments are supposed to do, which is provide free health care services. Rather than pay for inferior public services, people naturally preferred the higher-quality and more responsive private provision. The proliferation of private facilities of all sorts made the ‘exit’ from public provision fairly easy. Private providers in the highly unregulated health markets of poor countries are more than happy to provide their clients with the services they want, not necessarily those they need. In the 1990s, Susan Reynolds Whyte found that people in rural Uganda could turn up at drug shops and ask for whatever medicines they wanted in proportions they themselves had determined, in line with the amount of money they had. The Bamako Initiative therefore fell short of its aspirations because it was founded on plausible but questionable presumptions.

Why did community participation propositions such as the Bamako Initiative appear in the late 80s’? Could/should they have been designed differently?

The initiatives appeared at the time they did because there was a desperate need for change. Public provision of health services in much of the developing world was abysmal. There was need for radical thinking, to devise ways of bringing about improvement. Yes, they could have been designed differently. The key problem, as far as I can figure it out, was the one-size-fits-all approach, whereby development initiatives are introduced in every country in exactly the same way, without regard to contextual considerations. Clearly countries are different and cannot possibly follow the same path in the pre-determined ways the development industry promotes. There is something to be said for each country trying to do what fits its context rather than going for so-called ‘best practice’. If countries such as Rwanda have been more successful than others in reforming their health systems in ways that have proved to work for them, it is because, as research by the Africa Power and Politics Programme at the Overseas Development Institute discovered, they went for “good fit” rather than ‘best practice’ solutions. They provide us with the grounds for questioning the tendency within the development industry to promote universalist solutions to problems of development or governance.

You have been a critical voice of community participation and incidentally you come from Uganda - unlike quite a few prominent researchers on community participation who come from North America/Western Europe. Do you think there is a (Western) "doxa" of community participation? Was it mostly a donor fad?

As I indicated at the beginning, my skepticism about participation stemmed from my understanding of how the community I was born in and grew up in functioned, and how things such as leadership were understood. It never derived from theorizing about what is good for poor communities. The trouble with the development industry is that it is dominated by theorists whose understanding of the world or worlds they want to change or improved is limited and informed by short visits and to a large extent superficial interactions with the people whose lives they want to improve. It seems to me as if the problem really is the naïve liberalism of well meaning but misguided outsiders working with insiders who are too willing to play along without asking some hard questions. In my opinion the Rwandans get a lot right by refusing to be dragged along, by questioning and rejecting things they believe will not work for them and going for what works.

Do you think it would make sense to consider using similar mechanisms of community participation in North America/Western Europe?

I don’t think so. For one thing, participatory mechanisms demand lots of people’s time. You cannot expect people in a community to hold all these meetings and make all the decisions; what time would they have left for ‘living’? I have lived in Europe. I never sat in a single community meeting and if anyone had required me to attend as many meetings as my mother in the village in Uganda is required, I would never have had the time to do so. My mother attends very few meetings and misses most for the same reasons. Things in the areas of London where I lived, worked the way they did because the UK has a functioning state. That is what we need in Africa and the developing world, not participation. This is not to say that participation has no value; it does. It can complement a strong, functioning state when people could rise up and express dissatisfaction whenever they may judge it necessary. And in that case, it can only be sustained in a context where the state is responsive. Otherwise people will see no reason to engage in citizen action that produces no results.

If I understand correctly, community participation in social services in Uganda was also quite heavily promoted by the state. What do you think is

the reason? Wasn't it in a sense weakening the state a bit more?

As a fashion in development, participation coincided with the rise to power of the National Resistance Movement (NRM). The NRM leadership had tested the benefits of citizens participating in decision making during the civil war when they organized citizens into local councils in order to enable them to take charge of things such as security and also to vet recruits into the rebel army. The arrangements worked well enough for the Movement to want to apply them to post-war governance once they seized power, not least because they offered a window of opportunity for the state to penetrate the entire countryside, undermine traditional authority structures and entrench itself. Further, the NRM’s rise to power coincided with the early post-cold-war period when democratization and accompanying phenomena such as decentralization were top on the agenda of the donor community. In this sense there was a coincidence of interests between the NRM leadership and the donor community. Two decades down the road, we know that there was a great deal of naivety in assuming that ordinary people actively wanted and were capable of watching over their leaders and questioning as well as directing their activities. I do not think participation weakened the state. Rather, it did nothing to strength states that were already weak. It allowed governments to shirk their responsibility for making things work and to load it onto citizens who possessed neither the inclination nor the capacity for doing so.

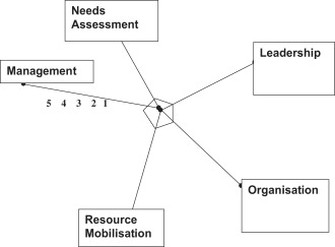

In a recent article, you argue that "vertical and horizontal co-ordination, inspection and supervision, and the strength of accountability enforcement mechanisms" are the keys for efficient social services delivery. What is exactly the role of communities there? What is the future of community participation in social services delivery?

Yes, indeed, those are the keys in my opinion. Communities ought to be accorded avenues through which they can pressurize their leaders if they judge that to be the thing to do at any one moment. This could happen if, say, they find the quality of service provision is below their expectations. For this to happen, educational campaigns should be mounted to ensure they know it is their right to do so. This is more or less the situation in Western democracies. People are not required – and I mean required – to participate in decision making on the scale those in poor countries are. However, when leaders make decisions they find objectionable, they have the right to demonstrate or engage in forms of citizen action that put their message or messages across to whoever they are intended for. Even then, we should not expect this change to happen overnight. The kind of activism we see in advanced democracies took root over long periods of time.

It seems to me that popular participation is rarely considered as a political act. From your research and experience, would you say that popular participation is a political act?

Well, if we agree that participation is intended to influence decision making and in a sense even resource allocation, then it is about making a choice between or among competing ideas. It is therefore a political act. That in a sense is also a reason why it is a difficult proposition in contexts where relations between leaders and the people they lead are highly hierarchical and don’t entail direct confrontation or contestation.